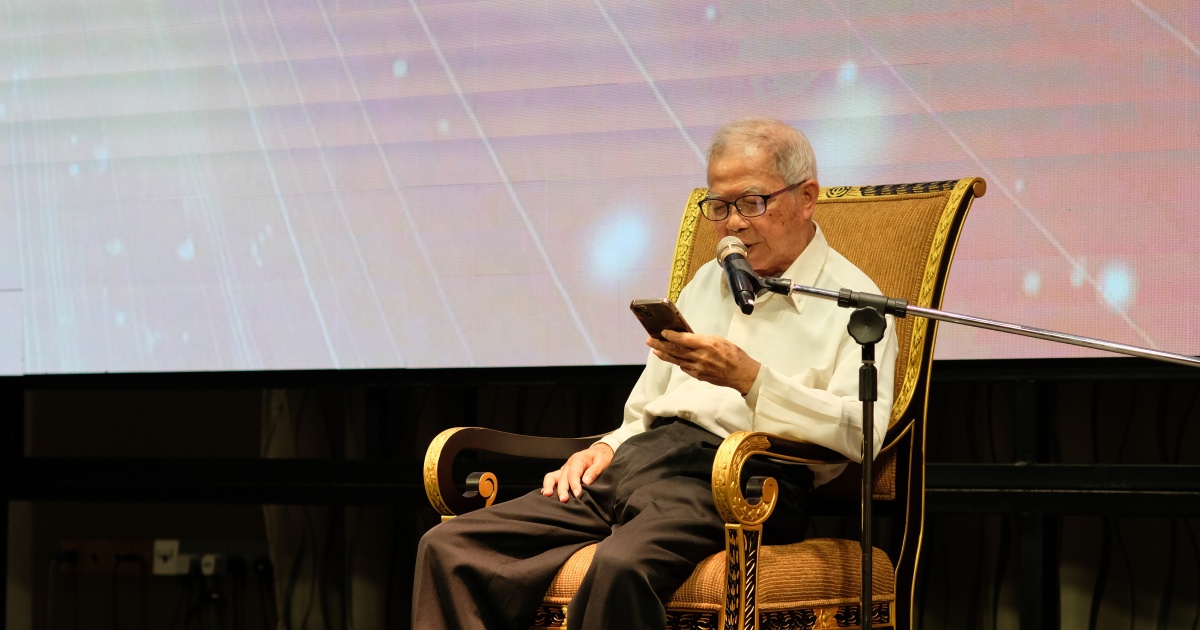

Author: Chong Chee Wai

Recently, Malaysia witnessed a tragedy that echoed the British Netflix crime miniseries Adolescence—a shocking and heartbreaking incident that felt almost cinematic in its horror. Many of us find it difficult to comprehend how a 14-year-old could commit such an act. The emotions that arise—disbelief, sorrow, anger, helplessness—are immense and tangled.

When an unthinkable tragedy happens, our minds instinctively search for explanations to make sense of it—to find control, to soothe our anxiety. The easiest explanation is often to blame the family, to assume it’s a matter of parenting failure.

But Adolescence offers another perspective. In the show, the protagonist’s father had experienced domestic violence as a child. Yet as an adult, he consciously avoided passing that violence on to his son. The mother, too, was warm and caring. The family was ordinary—loving even—suggesting that not every tragedy is rooted in the “original family problem.”

The story instead explores how a teenager can be consumed by a toxic mix of chaotic school life, social exclusion, online bullying, misogynistic internet culture, identity struggles, and the erosion of real-world connection—ultimately collapsing under the weight of it all.

We crave simple explanations—blaming the family, the school, the Ministry of Education—because doing so gives our minds a place to rest. But in truth, when an avalanche happens, no single snowflake is innocent. Tragedy is rarely caused by one factor alone.

If we are willing to accept the complexity—to face and examine the ecosystem in which modern youth live—we begin to see what we’ve overlooked: that today’s adolescents exist in fragile, anxious, and confusing environments. Many live more in the digital world than in reality, resulting in a disconnection between mind and world. Their developing brains, combined with exposure to toxic online culture, distort how they perceive relationships, sexuality, self-worth, and emotions—leaving them vulnerable, lost, and detached from reality.

Author of The Overexposed Generation, psychologist Chen Pin-Hao, once said:

“They grow up in the safest era in history, yet they have the lowest sense of psychological safety.”

The rising number of youth-related crimes should serve as a warning: our current education and justice systems are not keeping pace with the challenges of this generation.

Our justice system needs targeted youth laws—specifically concerning juvenile cyber laws, anti-bullying legislation, sexual harassment, school safety and mental health—along with neutral reporting platforms so young people can seek help safely and confidently. Most importantly, enforcement must be real and effective.

Our education system also needs reform. Foundational knowledge is important, but in an age of AI and endless information, what youth truly need is guidance—on how to think critically about what they read online, how to reflect on digital culture, how to understand their emotions and mental needs, and how to assess what’s real and what’s not.

To help youth strengthen their sense of reality and cope with modern challenges, the education system can be restructured to include the following areas of learning:

- Juvenile law education (from ages 12–13)

- Interpersonal interaction, romantic relationships, and how to deal with bullying (physical, social and online)

- Digital literacy and MCMC cyber laws

- Sex education and knowledge about STDs

- Adolescent brain and physical development (to prepare them for puberty; should be taught before age 13)

- Critical and reflective education (through debate and discussion, students learn to recognize and reflect on the consequences of actions, as well as the influence of online information and digital culture)

- Help-seeking and reality awareness

- Mental health and awareness of neurodiversity (understanding neurodivergent individuals)

- Respecting differences and conflict resolution

- Mindfulness and emotional literacy

These subjects can empower youth to deconstruct misinformation and toxic culture, develop resilience and cognitive clarity, and navigate relationships and anxiety with maturity and compassion.

In the film Good Will Hunting, the psychology professor Sean tells the genius protagonist Will:

“So if I asked you about art, you’d probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written.

Michelangelo—you know a lot about him.

Life’s work, political aspirations, him and the Pope, sexual orientation, the whole works, right?

But I’ll bet you can’t tell me what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel.

You’ve never actually stood there and looked up at that beautiful ceiling.”

“If I asked you about war, you’d probably throw Shakespeare at me, right?

‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends.’

But you’ve never been near one.

You’ve never held your best friend’s head in your lap and watched him gasp his last breath, looking to you for help.”

Sean wanted Will to understand that knowledge without real experience is hollow—that true growth comes from connection, empathy, and humility before life itself.

Our teenagers today are like Will—they know so much, yet feel lost and helpless.

Parents—it may not be your fault. But for the sake of your children, you can still try:

- From early childhood, spend real, physical time with your children—play together, decorate the home, do household chores, and engage with plants and animals. These hands-on activities help nurture their sense of reality and connection to the physical world.

- Continue to show care and build an emotional safety rope—maintain consistent affection and communication so your child feels secure and knows that your relationship is a safe and dependable space.

- Have the courage to discuss—or use games to explore—real-life and social topics such as rejection, online bullying, sexual curiosity, and romantic relationships. These conversations help them understand emotions, relationships, and boundaries in a healthy way.

- Remind them that they can always seek help from you or designate a few trusted adults as safe figures they can turn to. And most importantly—when they do reach out, listen without judgment or preaching. Stay with them, accompany them through the difficulty, and let them feel seen and supported.

Every era comes with its blessings and burdens. We are not gods — we can’t fully protect our children—but we can learn, support, and walk beside them.

Finally, to all parents and adults affected by such news:

Take a deep breath. Acknowledge your sadness, fear, or anxiety. Treat your emotions gently. Seek support when you need it.

May peace be with the victims, the departed, and the grieving families.